Platform6Documenta11 Recently

‘Thinking Documenta, Doing Documenta’: mulling Documenta11, Platforms 1–5 (2002)

CloseChapters

- Back to Top

- The World Turned Upside Down: art and et...The World Turned Upside Down: art and ethics in the rise of the “Stone Age South”

- The World Turned Upside Down: art and et...The World Turned Upside Down: art and ethics in the rise of the ”Stone Age South”

- Hanni Kamaly: Markings – A Discursive ...Hanni Kamaly: Markings – A Discursive Walk through Malmö(Re)Makers of the Apartheid-era Art History Room: Students Sebastiao Borges, Ellinor Lager, Max Ockborn, Joana Pereira, Joakim Sandqvist

- The AAH Room – A Re-enactment in Sever...The AAH Room – A Re-enactment in Several Acts

- AnnotationsAnnotations

- References

‘Thinking Documenta, Doing Documenta’: mulling Documenta11, Platforms 1–5 (2002)

Documenta11 was a rub-up of four discursive platforms against a fifth, a culminating visual arts practice platform, an exhibition. Looking back on it – not least, in several discussions with Okwui – we began to ponder the limits of the dual structure – ‘Thinking and Doing’. We felt it had been indispensible for creating the circumambient air of ideas and concepts for the exhibition. But had it perhaps unwittingly come to suggest a slightly too hard and fast divide between the discursive and visual art activity. Could we imagine the relationship between theory and practice in less Cartesian, more nonbinary terms? Did the D11 divide of Platforms inadvertently give the impression that visual art practice simply drew upon readymade bodies of knowledge, idea and theory, philosophy, politics and the like rather than that it was an active mode of knowledge production in its own right? ‘Thinking and doing’ do have their autonomous moments and spaces. But alongside we had to spotlight visual art knowledge production as the vital entangled interaction of ‘thinking in and through art practice’.

At the opening of D11, an early probe along these lines was the ‘Discursive Picnic‘ held at the Orangerie, Kassel and beyond on the banks of the Fulda. Later at Hofgeismar (2005), then, it would go on to be more rigorously tested in numerous events-ideas exchanges across the world.

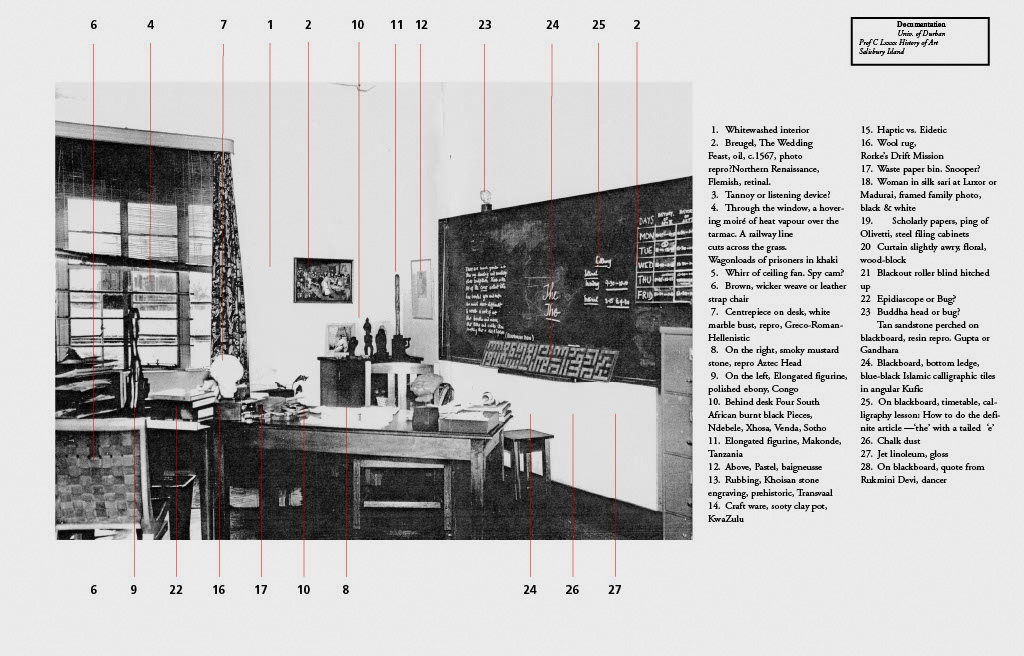

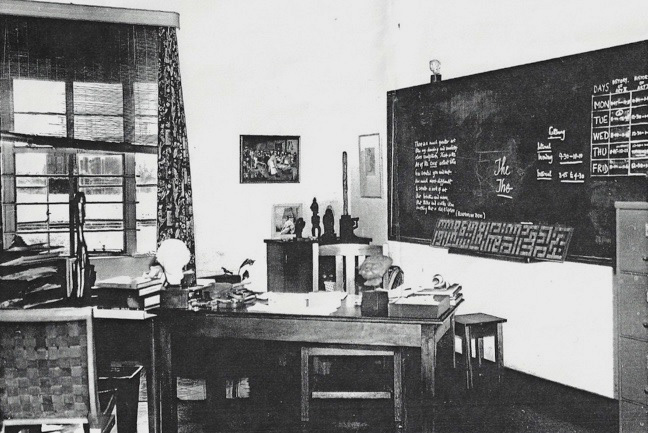

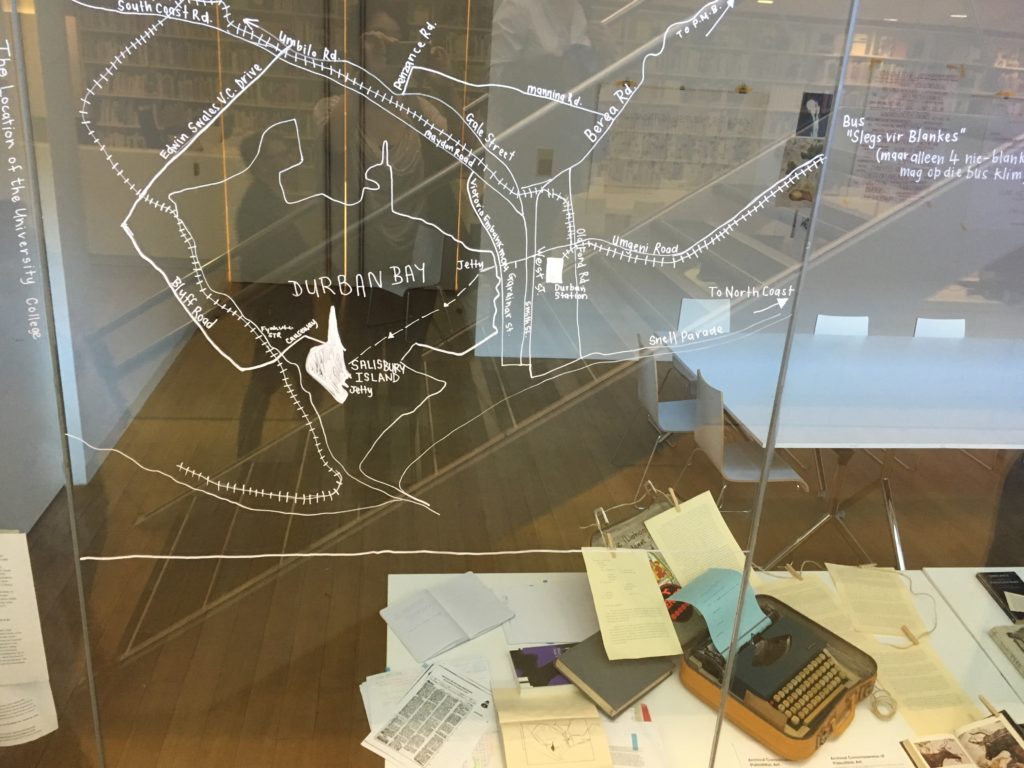

A key project for airing the theory/practice poser – ‘visual art practice as a mode of knowledge production’ – was the reconstruction or re-enactment of the Apartheidera Art History Room on Salisbury Island, Durban at the University College for Blacks of Indian Origin. The AAH Room marked a historical highpoint in the Apartheid government’s segregation of all educational institutions according to race, colour and ethnicity. The AAH Room reconstruction/re-enactment was of a slightly blurry photocopy of a archive photograph of the room obtained with some difficulty from the University archive by Clifford Charles, a South African artist, who had worked with Okwui on the Johannesburg Biennale (1997) The image of the AAH Room is a copy of a photocopy of a photograph most likely taken in 1971. This was on the eve of the University’s move to the new segregated campus at Durban-Westville. With the end of Apartheid, it would be desegregated and reconstituted as the University of Kwa Zulu, Natal.

The AAH Room ‘reconstruction’ was occasion to explore a range questions: Approaches to ‘critical difference’ versus the Apartheid treatment of ‘racialised difference’ versus the rise of multicultural managerialism in Europe.

Systems of assimilation through programmes of ‘diversity and inclusion’ in today’s the culture and creative industries.

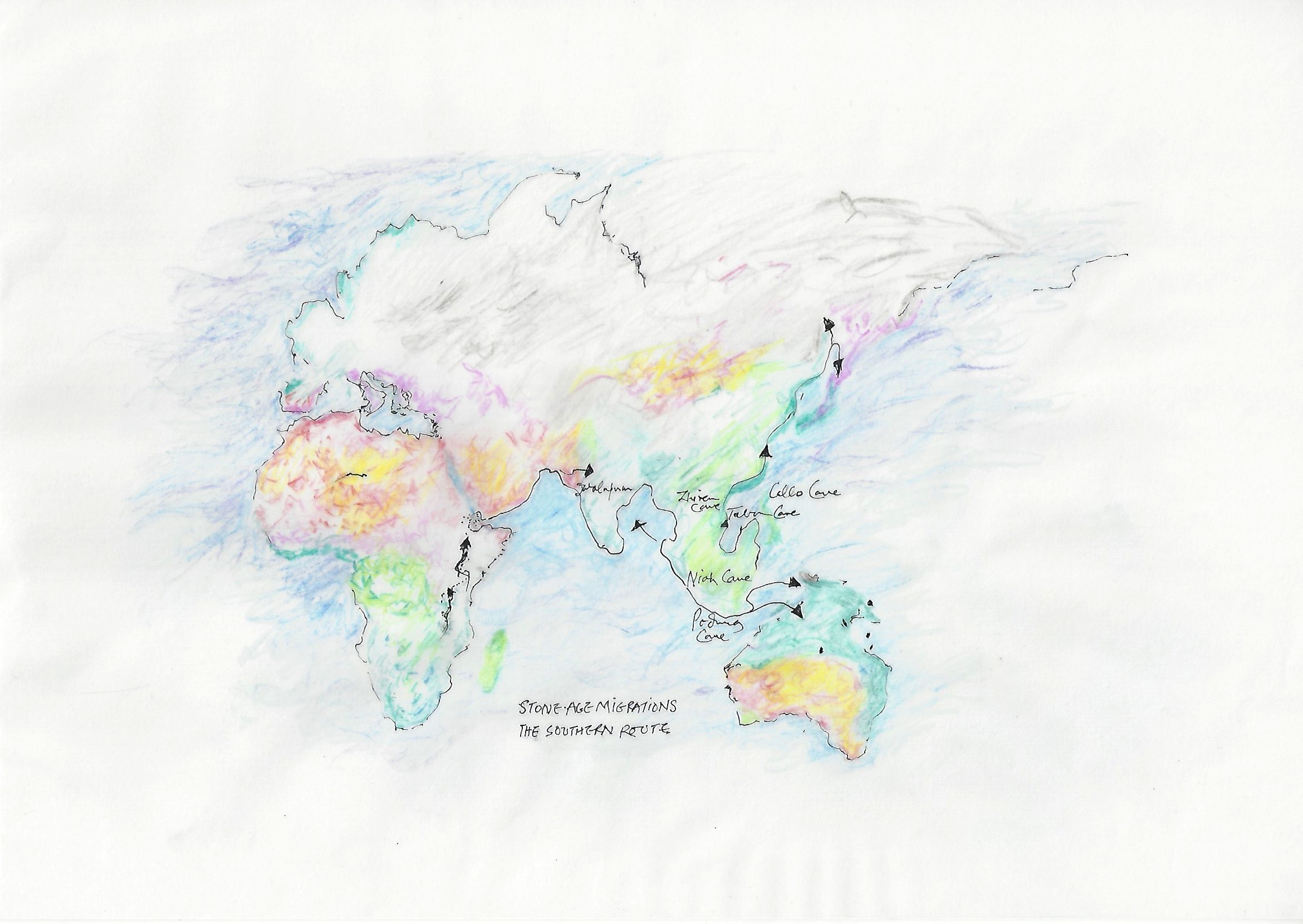

Prehistoric migration and Prehistoric art of the Drakensberg, Natal amongst other themes.

The central thread: If visual arts are a form of knowledge production what sort of knowledge does it produce? How can it engage with other academic discipline without simply mirroring them? What is its ‘critical difference’ Vis à vis other academic disciplines? What sort of knowledge is produced in the process of thinking through visual art practice'

The following are images and texts related to the series of reconstructions:

Pretoria University. 2014 – deferred

Malmo Art Academy. Lund University. 2017

Maumaus, Lisbon. 2017

Stedelijk Museum + Amsterdam University. 2018

Antwerpen Art Academy. 2021. Ongoing and pending

© Ecke Bonk / Courtesy of the author

The World Turned Upside Down:

art and ethics in the rise of the “Stone Age South”

The thrust of today’s migrations seems largely ‘Northward’ – even in the Antipodes where they are clearly headed towards the opposite pole. The ‘South’ has tended to signal ‘underdevelopment and crisis ’. It has also flagged up notions of ‘other possibilities, alternative perspectives’, other ‘designs for living’. The ‘exodus from the South for the North’ is at odds with the idea of ‘Global South’ as a privileged vantage point from which to critique the world-system. We have rather anomalies and crossovers that affirm and straddle, unpick and unravel in one go received N/S dividing lines. How to map this topsy-turvy global space, how to take its sound?

On the one hand, with today’s migrations the classic, cardinal points and domains – ‘East/West/ North/South’ – are constantly fixed, even vehemently asserted. On the other, migratory drives surge and spill over such distinctions blurring and undoing them—throwing up fresh contact and interaction. Do these emerging spaces mirror strands of the ‘primordial, pristine’ space into which our ancestors, stone age homo sapiens, wandered ‘out of Africa’ to roam and rove what were the ‘proto-continents’? An ‘unnamed’ space prior to demarcations and orientations – a pre-cardinal space – should we say? Does it echo the rising ‘post-cardinal’ spatial mentality and experience thrown up, against the odds, by today’s migrations? With this streaming movement do we have the glimmerings of a ‘contemporary paleolithic non-cardinality’?

The start-up for our project is a ‘reconstruction’ of the Art History Room (Durban, South Africa) of the Apartheid years. The AH Room was at the University of South Africa, University College, Durban for Blacks of Indian origin. This is in the province of Natal with the great Drakensberg mountain range – Ukhahlamba – with one of the world’s most extensive sites of prehistoric rock art and cave paintings. The ‘reconstruction or recreation’ at Malmo, Sweden can be in any mode – art installation, film, diagrammatic or performative statement, walks, discursive picnics, critical rambles etc.

The AAH Room put on show an ‘evolutionary ladder’ of artefacts, artworks and cultures from across the world. Its effect, if not explicit objective, was to underline a Eurocentric vision of things – not uncommon in art studies of the time. Some took it to imply that the spectrum of world cultures and art forms existed in separate, segregated compartments, almost in ‘parallel universes’. To their eyes the display embodied ‘apartness’ – sometimes touted as a ‘multicultural’ rainbow (in which, needless to say, some cultures were more equal than others)

But did the display also open up – perhaps quite unwittingly – counter-views and alternative readings? A glance across the room inescapably brought into play notions of mix, exchange, and swap – the sense of brisk translation between diverse artistic and cultural idioms, styles, and modes of thinking. What light could this throw on today’s world of the migratory swirl of peoples and cultural elements – on prickly issues of ‘multiculturalism, its limits and shortcomings’, on questions of living with ‘diversity, difference and multiplicity’, on much-thumbed notions of ‘hospitality and tolerance’, on ceaseless everyday cultural translation and cosmopolitanising forces – all in a setting of apparent ‘racisme sans race’?

Our explorations will link up studies of the Swedish anti-apartheid archives – ranging over issues of South African/Swedish women, ‘minorities’ and their ‘overlooked’ place in representations of the historical struggles; North/South prehistoric, parietal art, contemporary ancestral and aboriginal presences. The AH Room had evoked the idea of a world art system: in some ways, it tended to mirror Andre Malraux’s cosmopolitan views of art and culture in a ‘museum without walls’. Today, does the development of the global museum – hand in glove with contemporary creative industries – see the makings of flat-pack, ‘globalised’ art practices across our art education institutions, galleries and museums?

© Gertrud Sandqvist, Sebastian Borges, Ellinor Lager, Max Ockborn, Joanna Pereira, Joakim Sandqvist / Courtesy of the author

Alongside to mull: The AH Room had come into being in Apartheid’s segregating, ethnicising logic: at the time, opposition to this was summed in the slogan: ’Knowledge is Colour Blind’. What to make of this in the face of today’s search for a ‘decolonialisation of knowledge’ – for ‘tonal modes of knowing’ – not least, in the 3 thick of an all-encompassing knowledge society, the drives towards a pansophic world? What mileage for art practice, creativity and art research not simply as hard-nosed ‘knowledge production’ but perhaps its opposite – as modes of ‘knowledgeable ignorance’, as ‘Ignorantitis Sapiens’?

SCM

November 2016

London. Lund

© Sarat Maharaj

© Gertrud Sandqvist, Sebastiao Borges, Ellinor Lager, Max Ockborn, Joanna Pereira, Joakim Sandqvist / Courtesy of the author

The World Turned Upside Down:

art and ethics in the rise of the ”Stone Age South”

Malmö Art Academy 31.1 – 6.6 2017

Lecturers:

Professor Sarat Maharaj: After the Apartheid State, Beyond Cardinality: Neither North/south nor East/West. the Paleolithic and the Contemporary Today’s Migrations (Inauguration lecture 31.1)

The Drakensberg Prehistoric Cave Paintings and the Retinal (March 20)

Acoustemics and the Decolonialising of Knowledge (Closing lecture June 6)

Professor Matts Leiderstam: The Gift of Tears (February 2)

Professor Franco Farinelli: On the Nature of Mapping ( February 3)

Senior lecturer Jan Apel: The Scandinavian Pioneer Settlements (February 6)

Ndikhumbule Ngqinambi: Artist talk ( February 10)

Junior lecturer Margot Edström: The Activists , SAFRAN group and Skåne archives of anti-apartheid groups, (full day seminar February 15)

Professor Paul Gilroy: A Proper Name for Fascism: Torture , Humanism and the Challenge of Translating Inimba ( February 20)

Professor Emily Wardill: Screening and presentation of Fulll Firearms (February 20)

Professor Thomas Higham: Migration, Extinction and Colonisation in the Palaeolithic Neanderthals, Denisovans, and Modern Humans (February 27)

Jürgen Bock: Tout-Monde, Négritude and Maison Tropicale (3-day seminar March 1–3)

Hans Carlsson, Runo Lagomarsino,Julia Willén, Jakob Jakobsen, Patricia Lorenzini: Unsettling White Temporalities, lectures and seminars (March 9-10)

Dr D G Govinden: The World Turned Upside Down – A view from the South ( April 4–6)

Angela Ferreira: Artist talk (April 4)

Professor Arathi Sriprakash: Decolonising Minds? The Global Politics of Knowledge (fullday seminars and lectures, April 20–21)

Professor Gertrud Sandqvist: The Daughter of Cosmos, on artist and theosophist Rukmani Devi (April 27)

Manuela Ribeiro Sanches: Disorienting Europe: Reading Cesaire and Fanon on the Twenty-First Century ( full-day seminars May 2–4)

Hanni Kamaly: Markings – A Discursive Walk through Malmö

(Re)Makers of the Apartheid-era Art History Room:

Students Sebastiao Borges, Ellinor Lager, Max Ockborn, Joana Pereira, Joakim Sandqvist

by Gertud Sandqvist

The point of departure of this big project was a reconstruction of the room in which Professor Sarat Maharaj learned art history during the Apartheid era at University College of South Africa for Blacks of Indian Origin at Salisbury Island, Durban. A slightly blurred photocopy of a photograph of the AAH Room was a study in ambivalence. The references to art in this room during the Apartheid regime in South Africa were much more global than a class in art history in the UK would be at the time. On the other hand – the peak of achievement was still “obvious” . It was the white plaster copy of a classical Greek sculpture.

The room was reconstructed at the Malmö Art Academy by a group of students during Autummn 2016. The very impossibility to make an exact reconstruction from a rather blurry photo i b/w shows important insights in how human communication is operating. It was interesting to follow the decisions made by the students when they reconstructed in particular the sculptures in the photograph. In the end they looked as remnants from a late, degenerated style of – something. The supposed sharp difference between the different time periods and areas where the objects were made was blurred – indeed it is impossible to trace the origins. But the students didn’t want to make a point out of this. It was a consequence of how the different layers of reproduction corresponded with how recognition works: if we don’t understand, we guess.

The reconstruction of the rest of the room followed similar lines. The students found furniture that resembled the ones in the photograph, given the distance between Salisbury Island in the 1960:ies in Durban and the flea-markets in Malmö fifty years later. Sometimes the students managed to find a relatively accurate copy: the carpet seen at the photograph was actually commissioned of a Swedish Mission Station in the area, and the students managed to trace it back to Sweden.

The room hosted a number of lectures, seminars, workshops and screenings with the point of departure in the project description given by scholars, artists, activists around the themes of migration, present and 50 000 years ago, colonialism, womens’(pushed aside) role when it come to the writing of South African Anti Apartheid history, and a decolonizing of knowledge production.

For Malmö Art Academy this is by far the largest project we have done, this far. Professor Maharaj being a most valued member of the faculty made this endeavor possible. Through the project some 50 students got a glimpse of an insight in a time and a situation different from theirs- and yet not. Sweden had both through missionaries in the 1950:ies and through a number of anti-apartheid groups with a more socialist background in the 1960:ies- 70:ies an almost first-hand experience of the brutal Apartheid system. Many of the ANC leaders visited Sweden for longer or shorter periods, and the boycott of goods from the South African Apartheid economy was a source of national pride. It turned out that many of the activists of the time were still around. It was our pleasure to invite them for seminars where they met with a new generation of activists, exchanging experiences, differences – and similarities.

Through the collaboration with our longstanding partner Maumaus in Lisbon the project also opened up towards the complicated relations between different kinds of colonialization, and the precarious role the Portuguese from Moçambique had in apartheid South Africa. Artist Angela Ferreira was one of those. Through Maumaus and its director Jürgen Bock and his collaborator Manuela Ribeiro Sanches the students in the project got valuable insights in the Portuguese/French experience and understanding of colonialism.

But of course the mind-blowing experience of the participating students was mainly a result of the very wide lines of thoughts suggested by professor Maharaj, the initiator of the project. Anchored in the old photograph, he used detail after detail in it to depict new connections between cultures and civilizations. The world opened up. And closed down. As a young student he experienced the hard way that some places were forbidden for him under the Apartheid regime. Durban is in the province of Natal where are the famous Drakensberg caves, with their paleolithic paintings made by the San people. He could not join the study trip with Professor Walter Battiss as travel and accommodation facilities were for Whites only. Without the right kind of government documents the caves would remain forbidden to him though it was an essential part of his coursework. This small comment made in one of professor Maharaj’s lectures got suddenly the students to understand what apartheid actually means. Since the students came from different backgrounds they could start to discuss, and compare, and despair, and discuss again.

Why is it important for young artists to encounter such a widespread and non-linear thinking? Maybe because it shows that not only artists are thinking in a non-linear way. That would mean that they gain confidence in their own way of thinking. The experience of four months of intense meetings with highly sophisticated knowledge along an adventurous set of connections makes them respect knowledge other than their own. The blend of personal recollections and theoretical speculations makes them understand the entangledness of knowledge, politics, the personal and the beauty of the detail.

Is it important that they “understand”? Maybe not. Like all knowledge it fuels their thinking. It burns and disappears. Maybe something rests as ground for new thinking. As a pedagogue you don’t know. Maybe it was the surviving bumble-bee on the windowsill that really meant something.

The AAH Room –

A Re-enactment in Several Acts

by Jürgen Bock

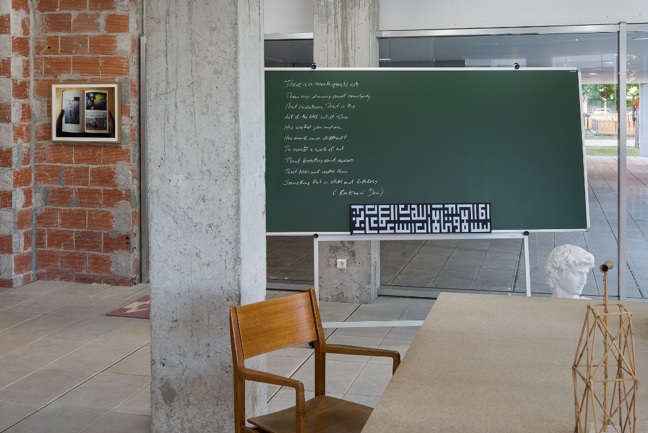

A black and white photograph, showing the office of Professor X – on Salisbury Island, Durban, South Africa, in the 1960s – is the visual point of departure. The academic title, era and place suggest a university at the time of apartheid. It is indeed an Art History room and the picture is presented to us by Professor Sarat Maharaj, who studied in this room at the University College Durban for ‘Blacks of Indian origin’.

In the rationalised northern world, there is the idea that the South has tended to signal ‘underdevelopment and crisis’.1 Some years ago, Portugal’s location in Europe, on the southern edge, was synonymous with the European financial crisis and its inherent migration of Portuguese labour to the centre and North of Europe. The AAH room migrated from the past to the present and from the South to the North, and then back again, from Malmö to Lisbon – a place on the threshold between Africa and Europe.

The reconstruction of the Durban Art History room in Sweden was installed in a seminar room at the Malmö Art Academy at Lund University. A group of students took on the challenge of deciphering the image mentioned above, which announces its own pastness so clearly. It was difficult to identify all the items that Professor X had gathered in the room, creating a specific atmosphere for the students attending. The larger items, such as a desk, some chairs and a large blackboard with a poem written on it, were the easier parts. We can also recognise a framed artwork on the wall, a reprint of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Peasant Wedding of 1567, combined with artworks of African origin. Bruegel was a printmaker himself and painted Peasant Wedding 79 years after the Portuguese rounded the Cape of Good Hope, called Devil’s Cape by sailors and which Manuel I, the then king of Portugal considered too negative.

In the 1960s Art History room, all kinds of artworks or references to art from all over the world were juxtaposed side by side outside the museum space – undermining any attempt at classification of ‘western European high art’ and ‘African or Asian low art’, or artisanal objects normally classified in an ethnographically reductive way. In its ‘private’ appearance, the room undermined what the ‘public’ concept of ‘race’ then stood for. The students experienced the co-existence, a ‘mutual becoming’ of things through an apparently ‘accidental’ juxtaposing of objects, which, because of the normative structures in place at the time, would normally not have been seen that way. Bearing in mind a possible eloquence through the specific placing of objects, it might be worth paying attention to how seminar rooms look in the context of art education and what kind of teaching could take place through the ambiance of a space, through the equipment of a space, through a ‘different’ notion of infrastructure. What kind of ideas could be provoked and engendered, independent from those provided through direct teaching, in such places of dwelling and encounter with theory?2

I taught at the AAH Room in Malmö. I felt uncomfortable about taking my place at Professor X’s desk. The chair wasn’t comfortable, but those who had reconstructed the room weren’t offended at me changing it for a more comfortable one. A rather large group was facing me from sofas, while my position up on a chair looking down at my listeners suggested a hierarchy, which I usually question in my seminars regarding authority in the context of the study of art and the art world as system.3 At the same time, it also felt like a play, a symbolic representation, in which I had to take on my role and in which my vanity at sitting on such an important chair, having the rather daunting role of bringing to life the AAH room in Malmö together with a group of students, in a teaching environment that appears a ‘simulacrum’ of teaching, was strangely appealing. I felt that I couldn’t move as usual, exactly because there was a role to be played. There always is, but here it was more specific, because I had to be even more careful not to emphasise my comments with bodily gestures, because of all the amorphous clay artworks around me, which represented the rather diffuse, undecipherable objects in the picture of the Art History room on Salisbury Island.4 And it was not ‘my’ room, I was a visiting lecturer dragged into an invoked past of a country far away, a time of apartheid and Professor’s X choices of objects of interests.

© Courtesy of the author

For this setting I had chosen to present a number of films for discussion: the first session was a ‘history class’ with the help of Jihan El-Tari’s film on Cuba’s epic involvement in independence struggles on the African continent. Cuba: an African Odyssey (2006) links Lisbon, the place where I live and work, with specific historical moments on the continent just south of Portugal, referencing, for instance, Che Guevara’s secret stay in the Congo in 1964/65 or ten years later the carnation revolution in Portugal with its subsequent independence of Portuguese colonies in Africa.5

With the help of films by the Mali born cultural theorist Manthia Diawara, I introduced Édouard Glissant’s philosophy of a permanent becoming through engaging with others,6 which I linked to Brackette Williams’s notion of a contact zone as the place from which all culture emerged.7 A further discussion focused on ‘counter nation-state building’ through culture by Léopold Sédar Senghor’s concept of ‘Negritude’, with its ‘asymmetrical parallelism’, which seeks to combine the culture of the coloniser with the culture of the colonised, the latter seeking to overcome the former by merging with it in order to deliver itself in a new independent state. In the film Negritude – a Dialogue between Soyinka and Senghor (2012), Diawara relates a dialogue between the Nigerian Literature Nobel Prize laureate Wole Soyinka and Senegal’s first elected president Léopold Sédar Senghor British and French colonialism through a filmic re-enactment to problematise the by colonial regimes imposed – with different intensities – and from Brackette Williams’ perspective mistaken, idea of an absolute pure culture onto the colonised, which resulted consequently in just other, also specific, contact zones.

On the last seminar day, an art project was presented against the backdrop of the AAH room: in 2007 I curated Ângela Ferreira’s Maison Tropicale installation for the Portuguese pavilion at the 52nd Venice Biennial. I introduced the project as follows:

“Ângela Ferreira’s Maison Tropicale reflected on colonial history and its contemporary, post- and neo-colonial resonances. Amidst the territorial reorganisation undertaken by the colonial powers in Africa after World War II and following a public tender process, the French Overseas Ministry, through collaboration with the French designer Jean Prouvé, saw the possibility to further develop modernist ideas of conceiving a series of aesthetically sophisticated homes, that could be mass-produced and that would give people greater access to welldesigned, high quality architecture based on prefabricated aluminium modules. Prouvé’s ideas never took hold in Europe, but the possibility to install a large number of his houses in the African colonies led to the development of his Tropical House. Of the thousands of units originally envisaged, only three prototypes ultimately left Prouvé’s workshop. In 1949, the first Tropical House was transported by plane to Niger and subsequently installed in the capital, Niamey. Two other houses were transported to the Congo and installed in Brazzaville in 1951. With the (re)discovery of Prouvé’s ‘work’ in the 1990s, the houses also incited new interest and became part of a process of fetishisation of Prouvé’s productions by the design world. The three Tropical Houses were dismantled and transported to France where they were restored and subsequently presented there and in the United States, in a new context. This is what we know about Prouvé’s Tropical House, and it is at this point that the story of Ângela Ferreira’s Maison Tropicale begins. The installation at the Portuguese Pavilion in Venice presents us with the displacement of these houses, no longer located in France, the United States, Niger or the Congo, transforming them into ‘containers of history’, in transit between the worlds of the colonisers and the colonised, and – because the artist revives Prouvé’s link with Africa – between the decolonised and post-modern worlds with their realities of post and/or neo-colonialism. Ângela Ferreira recreates the places where Prouvé’s houses were installed, highlighting their absence and the traces left behind and evoking the structures themselves through the sculptural objects produced by the artist’s modular form of architecture that result from the accumulation of objects in a claustrophobic space and that remain permanently adrift.”8

La Biennale di Venezia, 2007

© Courtesy of the author

The sites hosting the AAH room in Lisbon and Malmö were rather different. It seemed that, after having had the opportunity to somehow ‘rehearse’ in and with the AAH room in Sweden, the project in Lisbon would be positioned ‘on a different stage’: an art gallery, with opening hours, a preview, press release, e-flyer and printed invitations. To a certain extent, the AAH room in Malmö engaged with such protocols – the room could also there be visited – but in Lisbon the AAH room was integrated into an ongoing schedule of exhibitions: before Sarat Maharaj’s project, Peter Friedl’s ‘Teatro Popular’ exhibition took place, and subsequently a group exhibition of five artists dedicated to the ethno-poetry of the German beatnik writer Hubert Fichte was to open. There was no hierarchy between Malmö and Lisbon, but the circumstances were different: a setting had to be created, which would function as a seminar room as well as an exhibition.

The way the space was produced was also different; the re-enactment in Malmö turned out to have been a prototype, from which one could learn and to which the Lisbon AAH room somehow responded, engaged with and, at the same time, distinguish itself from it. In Lisbon, available artworks were the starting point, together with purchased artefacts especially chosen for the exhibition. In addition, a table and a bookcase were needed, where the table in Lisbon indeed symbolised Professor X’s desk on Salisbury Island – a table the professor sits behind talking to the group of students gathered on the other side – but took precisely the shape a of larger table allowing a group of students to sit at ‘eye level’ with the teacher around the ‘desk’. The interpretations of Professor X’s office/seminar room on Salisbury Island developed through the symbolic staging in Malmö leading to a somewhat changed iteration in Lisbon.

For me, working as a curator with Professor Sarat Maharaj was rather different from all my previous work with artists. Instead of indicating this or that, this design and that item, this object and that artwork, when it came to rendering the blurred photograph back into life temporally in a space, Sarat Maharaj was rather subtle, commented carefully, mostly listening and encouraging to choose and arrange the objects in a way I understood to be the most appropriate. I realised how wonderfully easy it is to ‘obey’ artists’ demands, however difficult they may be. Responding to a rather open articulated context and a subtle given input, I became in a way a ‘medium’, myself being confronted with the creative act of going from intention to realisation through a chain of sometimes uncomfortable subjective decisions. Marcel Duchamp’s statement came to mind: ‘[The] struggle towards the realization is a series of efforts, pains, satisfactions, refusals, decisions, which also cannot and must not be fully self-conscious.’9

The core of the exhibition in Lisbon was constituted by two artworks by Heimo Zobernig, an artist whose practice engages with art’s infrastructures, turning equipment and objects for art’s display into art itself, blurring in a subtle way the thresholds between art and non-art objects. Often Zobernig’s artworks suggest a function, claiming at the same time the nonfunction of the art object, of an art for art’s sake. The sculptures created by him reference minimalism – Zobernig’s works are impeccable in their finishing, with a rigour not dissimilar to that of American minimal school, ironically contrasting the use of often raw industrial poor materials, such as particle board, of which Zobernig’s works at the AAH room were made.

The AHH room in Lisbon persisted as a re-enactment, where notions of the 25-year history of the Maumaus School merged with an interpretation of Professor X’s seminar room from the Salesbury Island 70 years ago. Because of a conceptual gap instigated by Sarat Maharaj, both were able to amalgamate in the exhibition space of Lumiar Cité.

Annotations

© Gertrud Sandqvist, Sebastiao Borges, Ellinor Lager, Max Ockborn, Joanna Pereira, Joakim Sandqvist / Courtesy of the author

A first image from the past, black & white, an image of an office/classroom – a section, a corner of the room, with a large number of objects. The image serves as an announcement of an unusual exhibition, which has at its core the display of an unusual seminar room. The same image exists with annotations, which are not revealed – annotations like an archeology about what is on the desk, written on the blackboard or hanging in the background above a group of African sculptures – the identification of a print of the painting The Peasant’s Wedding by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, curtains, a buddha and a bust made of plaster, a mix of what was not supposed to be mixed – low and high art, European, African and Asian art, and art references are assorted beyond any rule as the rule. Art, non-art and non-non-art objects, turning into a plentitude of objects of interests.

What follows here is the list of objects from the re-enactment of the AAH room in Lisbon combined with selected annotations: some objects mirror objects in Professor X’s office/seminar room at the University College Durban for ‘Blacks of Indian origin’, some are chosen associatively in a loose response to the original setting of the room from the 1960s, referencing the all-inclusive dialogue evoked by the scenery of a diversity of objects in the AAH room. The curatorial task was to devote oneself to an ‘activity of associations, contiguities, carryings-over to coincide with a liberation of symbolic energy’ (Roland Barthes).

Twenty-five chairs, a screen, sockets, a sound system and a table are welcoming the lecturer and participants of the seminars as well as the visitors of the exhibition. The latter might wonder who is supposed to sit here, to use this infrastructure on display, who will constitute the audience and who is supposed to talk from behind the desk? In the upper level of the gallery the projector appears as an object on its own among others in a dialogue with Durham and the south of Sweden, with the original and its first re-enactment at the Malmö Art Academy.

Oil on canvas, 60 x 67 cm

and

"Escultura da Casa" by Pedro Barateiro (2008)

Photograph, 158 x 127 cm

Deutsche Bank Collection

A canvas painted green with rough brush strokes was cut into four parts, one of which was integrated in the AAH room. Heimo Zobernig’s apparent speechlessness references a myth of modern abstract art which resonates in Pedro Barateiro Escultura da Casa. The eloquence of Barateiro’s photographic work – which depicts a modern bourgeois 1960s white shelf unit in an enlarged found image, isolated through rough brush strokes on top of the photograph – suggests the domestication of the savage of African art, displaying it as collectors’ modern trophies in western living rooms.

Gelatin silver print, 20 x 26 cm

Roger Palmer photographed the sign of a gas station in Wupperthal, South Africa. My hometown in Germany is Wuppertal, and I remember that I hated any change that took place in the town after I left and was not part of during my first years in Lisbon. The colonisers in Wupperthal had held on to the old spelling of a place, which had itself moved on, while the place in South Africa had too.

Lisbon, 2001

Cibachrome photograph

110 x 130 cm

Allan Sekula ‘discovered’ this circa 200- year-old device in the Lisbon Maritime Museum in 2001, some years before today’s migration tragedy in the Mediterranean Sea started. The instructions for the apparatus from a time when slavery was in full swing, starts with a poem, which Sekula had carefully displayed to be photographed in the jumble of the Maritime Museum’s storage.

Digital print, 58 x 74 cm

and

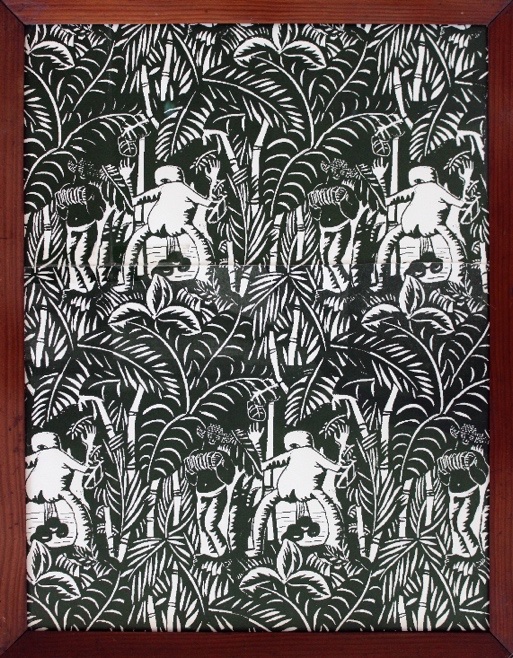

"Tapete Carpet from Elc Art & Craft Centre Rorke’s Drift" by Celiwe Maguhane, 2016

Karakul wool, 70 x 105 cm

The print was part of Renée Green’s exhibition with the same title at Lumiar Cité in 2016 and served as the motif for the invitation card. The text announcing the exhibition started with a quote by Jean-Luc Nancy: ‘How can we grasp the ungraspable character of passing? How can we grasp the pure conjunction of passing and presence, fleeing and stasis?’ Green engaged with variables of time and location, space and things, among reflections on relays, delays, movement, exile, migration, displacement and reinvention, all allowing for the contemplation of what arises amid particular combinations in a variety of conditions.

Print on paper, 46 x 35 cm

© Courtesy of the author

Print on paper, 46 x 35 cm

© Courtesy of the author

Emil Westman Hertz studied at the Maumaus Independent Study Programme in 2006 and had spent some time on the African continent as an adolescent. During his last days in Lisbon, he entered the director’s office with a print of a kind of Heart of Darkness stereotypical landscape. Figures with testicles resembling pairs of cherries appear as a pattern in a jungle. Emil offered Maumaus the print as a goodbye present with a broken frame he had found on the streets of Lisbon, which was repaired before displaying it for the first time in the AAH room.

Rukmini Devi’s poem, 120 x 250 cm

© Courtesy of the author

Rukmini Devi’s poem, 120 x 250 cm

© Courtesy of the author

Blackboard

Rukmini Devi’s poem, 120 x 250 cm

A modern freestanding blackboard references the Salisbury blackboard. After the end of the exhibition, the board was donated to a teaching association in Couva de Moura, a neighbourhood comprising vernacular architecture mainly erected by migrants from the African continent.

Object evoking Islamic calligraphic tiles in

angular Kufic, 2017

Acrylic paint on wood, 22 x 102 cm

The question was how to present the calligraphic tiles. In the Salisbury picture, the tiles appear upside down.

David, 2017

Plaster and fibreglass, 60 x 30 x 35 cm

Michelangelo’s David sculpture was unveiled in 1504, sixteen years after the Europeans set foot for the first time on – or should we better say returned to? – Mossel Bay in South Africa. Erected in a public space, it symbolised the defence of civil liberties. The statue’s eyes, with a warning glare, were directed at Rome. The bust of David at the AAH room in Lisbon had no particular target.

Makonde Buddha, n.d., south eastern Tanzania

Soapstone, 20 x 20 x 12 cm

Four chairs, Denmark, 1960s

90 x 80 x 65 cm each

Heimo Zobernig

Untitled, 1993

Particle board, 280 x 207 x 1.9 cm

6 trestles, pinewood, 74 x 37 x 73 cm each

Professor X’s desk on Salisbury Island was referenced in Lisbon by way of a large table by Heimo Zobernig.

Olaio

Office chair, 1960s, 90 x 50 x 60 cm

An object of contradiction: a 1960s chair from the renowned Portuguese furniture design company Olaio: the chair was reserved for the gallery manager and the lecturer during seminars.

Video on the commemorative celebrations of

the arrival of Bartomoleu Dias in 1488 in Mossel

Bay, South Africa, 1988, colour, 3 min. 50 sec.

The video documents the 1988 Bartomoleu Dias festival, a commemoration of the fivehundredth anniversary of the ‘rounding of the Cape of Good Hope’. In Portugal a replica of Dias’s caravel was built. To be able to arrive on time, it had to ‘sail’ with its diesel motor to South Africa. The staging of the encounter of the Portuguese with ‘natives’ on Mossel Bay beach close to Cape Town was a ‘particular challenge’ at a time when the beach was ‘for whites only’.

Bamboo, paper, thread and cardboard

53 x 45 x 14 cm

and

Curtain in capulana, Netherlands, 2017

280 x 320 cm

© Courtesy of the author

Sarat Maharaj highlighted the importance of curtains. It was an aesthetic feat to find an ‘African’ curtain that would work in the space. The material so commonly used in Africa tends to traditionally originate in the Netherlands, via Indonesia.

An image of a transmission tower erected in Mozambique, probably during the 1970s, instigates Ferreira’s work on Monuments and Utopias. As an artist operating between Europe and Africa, between modernist ideas of purity of expression and an ambiguity assumed by Ferreira as essential for an ’other’ modernism, she erected a reconstruction of a vernacular African tower, topped by a loudspeaker, in the middle of a park in Graz, Austria. The Monument, ‘the most public of all sculptures’, broadcast the Afrikaans Cape Sonnets by the Austrian/South African poet Peter Blum (1925-1990). Blum moved to South Africa from Vienna with his Jewish parents before the Anschluss. The sonnets were written in the 1950s in an Afrikaans slang spoken mostly by coloured people and thus by an oppressed part of the South African population, but also in a language shared by the oppressors and the oppressed. This Afrikaans slang was translated into the slang of other languages of local relevance in Graz. One of the sonnets closes the circle regarding questions of the Monument explicitly in its content: in his Cape Sonnet ‘Talking about Monuments’, Blum ironically described this kind of public art in South Africa dedicated to figures such Afduim-Murray as ‘thumbless’, Hofmeyr (‘wit paunch an’), Jan van Ribbeeck (‘dressed up like a Jintleman in his plus fours’), Cecil John Rhodes (‘points every day to de race course’) and also Queen Victoria in front of Parliament house, described by Blum as ‘ol, Miss Victoria wit’ her tiny little melon.’

Two-channel video installation re-edited to single-channel video, colour, sound, 17 min.

© Courtesy of the author

The Portuguese version of The Silver and the Cross was produced by Lumiar Cité/Maumaus in 2011. Harun Farocki asked for the dubbing of his voice and was enthusiastic about the voice of Manuela Ribeiro Sanches, a lecturer on the Maumaus Independent Study Programme. In the single-channel film, the image projected appears divided into two juxtaposed parts that are contextualised and complemented by a voice-over. ‘In this film/essay, Harun Farocki analyses the details of the painting Description of Cerro Rico and the Imperial Municipality of Potosí, painted by Gaspar Miguel de Berrío in 1758, which portrays the city of Potosí in Bolivia in great detail. Farocki’s voiceover is a discourse of Foucauldian archaeology, unfolding from the place and from the people involved in colonisation – the victims and the perpetrators, those who won and those who lost, the Amerindians and the colonisers for the Spanish crown, the forced and the free workers, the stonemasons, traders and craftsmen, the mine owners and foundry operators, the colonial administration and the clergy, the Spanish and their descendants.

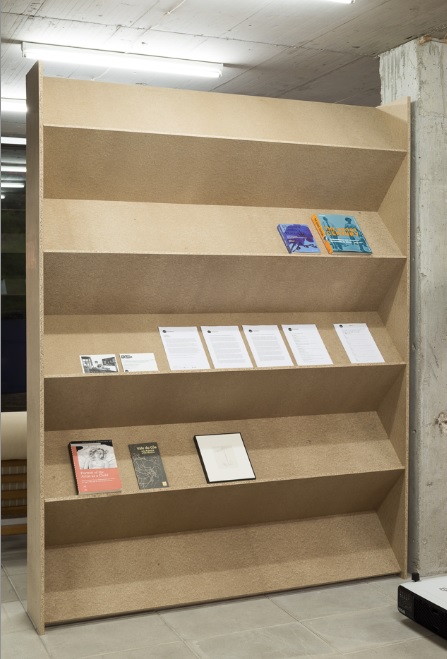

Particle board

267 x 200 x 34 cm

© Courtesy of the author

A modern minimalistic sculpture in poor material in the form of a shelf by Heimo Zobernig to ‘host’ all reading material selected by Sarat Maharaj for the visitors of the exhibition and the participants of the seminars – enabling study in the space when sitting on comfortable vintage Danish chairs from the 1960s. One of the books I added to Maharaj’s careful selection was Portrait of the Artist as a Child – The Gravettian Human Skeleton from the Abrigo do Lugar Velho and its Archeological Context, an academic publication on an archaeological find in Portugal, often referred to as ‘The Child of Lapedo’. An online magazine comments:

Buried for millennia in the rear of a rockshelter in the Lapedo Valley 85 miles north of Lisbon, Portugal, archaeologists uncovered the bones of a four-year-old child, comprising the first complete Palaeolithic skeleton ever dug in Iberia. But the significance of the discovery was far greater than this because analysis of the bones revealed that the child had the chin and lower arms of a human, but the jaw and build of a Neanderthal, suggesting that he was a hybrid, the result of interbreeding between the two species. The finding casts doubt on the accepted theory that Neanderthals disappeared from existence approximately 30,000 years ago and were replaced by Cro-Magnons, the first early modern humans. Rather, it suggests that Neanderthals interbred with modern humans and became part of our family, a fact that would have dramatic implications for evolutionary theorists around the world.10

Particle board

267 x 200 x 34 cm

© Courtesy of the author

© Courtesy of the author

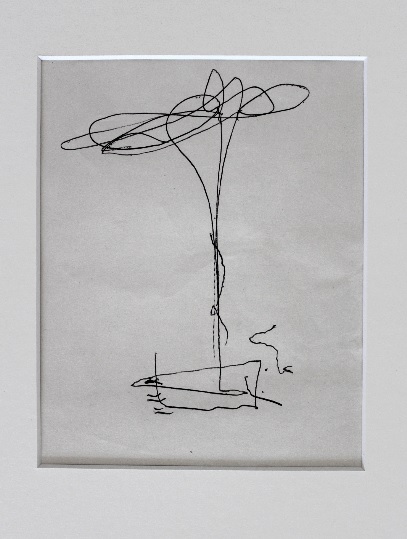

Only a drawing by an unknown author on Heimo Zobernig’s shelf, revealing a striking dynamic, an abstract form resulting from a certain velocity, with gestural lines suggesting a speed that recalls Cy Twombly.

© Courtesy of the author

© Courtesy of the author

The South African artist Roger Meintjes, with whom I had worked closely during the first years of the Maumaus Study Programme, returned in 1994 after the first free elections in South Africa. After Nelson Mandela was elected with an overwhelming majority, Meintjes had torn down one of the ANC campaign posters in order to bring it to Lisbon. One morning, he stepped without any comment into the director’s office, climbed on top of his desk and stapled the poster to the wall. With an English first name and an Afrikaans last name he did not have an easy adolescence.

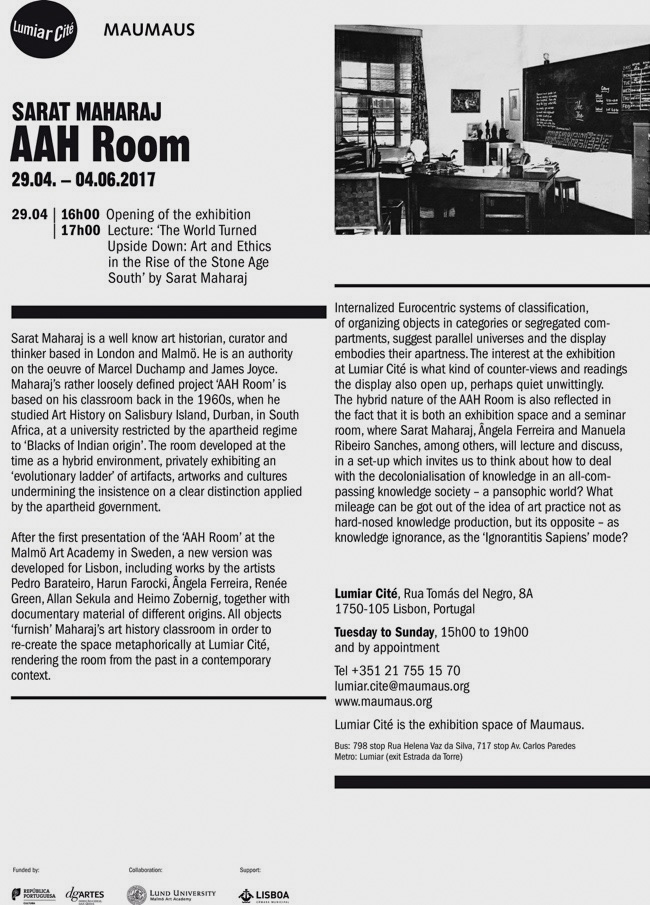

The exhibition ‘Sarat Maharaj – AAH Room’ was held at Lumiar Cité from 29 April until 4 June 2017. On the opening day, Sarat Maharaj gave a lecture titled ‘The World Turned Upside Down: Art and Ethics in the Rise of the Stone Age South’, which was followed by a two-day seminar on 1 and 2 May.

On 22-24 May 2017 Manuela Ribeiro Sanches held a seminar titled ‘Dis-Orienting Europe, Reading Césaire and Fanon in the 21th Century’. Filip de Boeck presented his lecture ‘“The Hole of the World” – Topographies of Urban Life in Central Africa’ on 16 May 2017. On 3 June 2017, Ângela Ferreira closed the lecture series with her talk ‘Each One Teach Each One’.

References

1

Abstract for Professor Sarat Maharaj’s seminar ‘The World turned Upside Down: Art and Ethics in the Rise of the Stone Age South’, January 2017.

2

Some Architecture campuses embody in their buildings’ appearance the discourses that are lectured and discussed, for example, Mies van der Rohes’ Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago (1956) and Álvaro Siza Vieira’s School of Architecture in Porto (1992).

3

Karl Mannheim wrote in 1928: ‘From this angle, we can see that an adequate education or instruction of the young (in the sense of the complete transmission of all experiential stimuli which underlie pragmatic knowledge) would encounter a formidable difficulty in the fact that the experiential problems of the young are defined by a different set of adversaries from those of their teachers. Thus (apart from the exact sciences), the teacher-pupil relationship is not as between one representative of “consciousness in general” and another, but as between one possible subjective centre of vital orientation and another subsequent one. This tension appears incapable of solution except for one compensating factor: not only does the teacher educate his pupil, but the pupil educates his teacher too. Generations are in a state of constant interaction.’ See ‘The Sociological Problem of Generations’, in Das Problem der Generationen (1928), reprinted as Chapter VII in Paul Kecskemeti (ed.) Essays on the Sociology of Knowledge (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1952) p. 301.

4

The rendering of the unfocussed items of African sculptures into ‘blurred’ clay works was done by Sebastião Borges, Joana Pereira, Ellinor Lager, Max Ockborn and Joakim Sandqvist – all students at the Malmö Art Academy, who created the AAH Room at the academy.

5

Jihan El-Tari, Cuba: an African Odyssey (2006, France, 190 min.)

6

Film by Manthia Diawara: Édouard Glissant – One World in Relation (2010, France, 50 min.).

7

Brackette Williams, personal correspondence with Ruth Wilson Gilmore, 24 July 2018.

8

Jürgen Bock, hand-out text for visitors of Ângela Ferreira’s ‘Maison Tropicale’ exhibition at the Portuguese Pavilion at the 52nd International Art Exhibition La Biennale di Venezia, 2007.

9

Marcel Duchamp, ‘The Creative Act’, talk given at the meeting of the American Federation of the Arts, Houston, TX, April 1957. Text originally printed in ART-news, Vol. 56, No. 4 (Summer), 1957.

10

See https://www.ancient-origins.net/humanorigins-science/controversial-lapedo-childneanderthal-human-hybrid-00903 (accessed 22 February 2021.